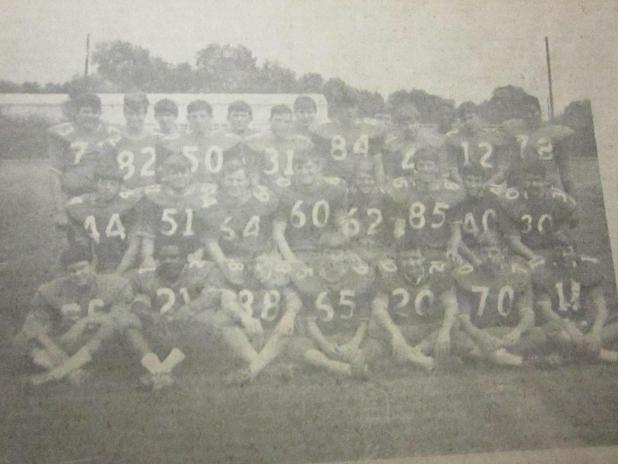

1970 COTTONPORT WILDCATS

It was the first year of “real” integration, and the Cottonport High Wildcats finished the historic year as the parish champions and its district champion, going 9-0 -- counting a loss to Ville Platte that became a win when Ville Platte had to forfeit its wins that season.

The members of that team were (front row, from left) Dick Callegari, Emile Celestine, Gary Bordelon, Lennie Lemoine, Greg Guillory, Kemp Thevenot, Peter Marchand, (middle row) Doug Chenevert, Chris Lemoine, Ike Riche, Robert Lemoine, Ralph Callegari, Roger Broussard, Andy Plauche, Todd Armand, (back row) Tommy Bordelon, John Davis, Billy Reason, Ronald Brouillette, Steve Galland, John Marchand, Mark Tassin, Rusty Jackson, Scott Merrick, Craig Riche, Larry Lacarte, Steve Ducote and Riley Francisco.

Two members of Cottonport High School's "fearsome foursome" backfield, fullback Todd Armand (left) and quarterback Steve Ducote, reminisce about the 1970 season. The other two members of the backfield were halfbacks Emile Celestine, who set a school rushing record, and Andy Plauche. Armand, Celestine and Ducote still live and work in Cottonport. Plauche has moved away from Cottonport.

Cottonport Wildcats of 1970 recall ‘year that should’ve been’

Almost a half-century ago, a group of boys played a game -- and played it well. They also showed that hate and bigotry, pain over losing a school and other hard lessons of life can be overcome when a group of boys becomes a team.

They didn’t win a state championship, but those who played on that team say they won a much bigger prize than that in 1970.

It was not an ordinary year. Previously all-black schools were being closed and consolidated with previously all-white schools when the federal government deemed the “freedom of choice” desegregation plans in place across the state were not eliminating the segregated school systems that had been established.

While there was bitterness and tension in some schools and communities hit by the changes, the transition “was very smooth here. We never had a single incident that was based on race,” then-quarterback Steve Ducote said.

The 1970 Cottonport Wildcats impressed a lot of people in a year when they went undefeated, 9-0, in the regular season.

The Class-A team actually lost to the larger Class-AA Ville Platte, 15-6. However, VPHS had to forfeit its wins that year due to playing over-age athletes.

“We should’ve won the game,” Ducote said. “We had two easy touchdown passes dropped. It ended up being counted as a win in the record book, but it never felt right saying we were undefeated that year.”

Ville Platte scored two touchdowns and a safety. The Wildcats had one touchdown.

The team won the 7-A district title and then defeated Greensburg High, 6-0, in the first round of the Class A playoffs. The hope of a state title ended when E.D. White High crushed the “Cats,” 20-0, in the quarterfinals.

Many believe 1970 was “the year that should’ve been” for the Wildcats. It led the state in rushing and then repeated the feat in 1971. Other Wildcat teams went further in the playoffs, but this team was special.

In 1987, Cottonport was party to another federal court desegregation/consolidation order, this time losing its high school grades and, with it, its football program.

However, even after 30 years the CHS alumni’s love for their school still runs strong -- at least as strong as Carver alumni’s love for their long-gone school.

WILDCAT MEMORIES

Three of the “year that should’ve been” Wildcat backfield -- Ducote, halfback Emile Celestine and fullback Todd Armand -- recalled that season and the social changes that served as the background for it.

The three were key players in the ‘Cats high-powered offense and still live in Cottonport.

Two other key elements of that offense are offensive lineman Joel “Rusty” Jackson and halfback Andy Plauche.

Jackson lives in Cypress, Texas. Plauche has also moved away from Cottonport. They could not be reached for comment.

Their coach, Causby “Bootsy” Watson, died in 2011. However, his reported comments from that year help to close the 47-year gap so that it seems like only yesterday.

Emile Celestine

Celestine had played football at Carver High School and came to Cottonport High as a 16-year-old junior. He quickly made his presence, and talent, known to Wildcat fans and foes alike.

"He, like all the rest, plays for one thing and that's to win,” Watson said in a 1970 interview. “There's no animosity. He likes them and the boys all like him. He's a good kid and you don't hear the bad comments. He is a Cottonport Wildcat."

Watson’s comments hint at the racial tension prevalent in other schools around the state.

“We had a situation where we were put to the test,” Celestine said. “It was a stressful situation, especially for the black students. We had been uprooted from a school that we were familiar with. Our brothers and sisters had gone to that school. Our parents had gone to that school.

“It was a feeling, not of anger, but something,” Celestine said. “We felt like that, but because of the kind of boys we were, the kind of upbringing we had at home and the kind of teachers we had at Carver, we were able to make adjustments and make that transition.”

He said that in those days, “it really did take a community to raise a child. Everyone was involved in our upbringing.”

While his years at Cottonport High were beneficial and enjoyable, he said the closing of Carver “hurt the black community overall. It was never the same. The school was the heart of the community.

“The same thing happened here in Cottonport when they closed the high school,” he added.

Celestine stood 5-8 and weighed 155 pounds, so he was not a “power back” by anyone’s definition. Still, the biggest boy on the team was Jackson at 195 pounds, so there wasn’t the discrepancy in size we see on today’s squads.

Watson summed up Celestine thusly: “This kid can break (away) any time. He’s so quick that a defensive man seldom gets a good shot at him.”

It was almost “love at first sight” when Watson saw Celestine run with the ball for the first time during pre-season drills that hot August of 1970. He immediately put the small speedster in the backfield, and assigned him No. 21 -- which had been worn by standout halfback Steve Andress, who had graduated the year before.

Celestine set his goal to surpass Andress’ school record for most yards in a season, but he kept the chase light-hearted.

“Coach, how do you expect me to gain 1,000 yards if I’ve got to watch the second half from the sidelines,” he jokingly asked Watson one week.

Celestine reached his goal, piling up over 1,000 yards that year and then breaking his own school record the next year.

As records have a tendency to do, Celestine saw his feat fall to Kelso Williams, known as “Special K” and the “Cottonport Cannonball,” who graduated in 1985.

While Celestine was a threat breaking out of the backfield, he was also deadly as a return specialist. He scored 17 touchdowns that year, 13 rushing and four on returns.

Celestine endeared himself to teammates and others with his genuine modesty.

In the locker room following his three-touchdown performance in the Bunkie Jamboree at the start of the 1970 football season, Celestine told an inquisitive reporter, “I didn't do anything but carry the ball, mister. If you want to talk to somebody, talk to those seven boys up front."

Today, Celestine still gives most of the credit for the Wildcats’ success to the offensive linemen.

“We had the highest average yards per carry in the state in all classifications, at 8.5 yards per carry,” Celestine said. “That is due to the hard work of the offensive linemen up front.”

Rusty Jackson

One of those “boys up front” was Jackson, a 6-1, 195-pound steam roller paving the way to the goal line for Wildcat ball carriers that season.

"A defensive man usually spends most of the night looking up at the stars when Jackson goes to blocking for Emile," Watson said in an interview that year.

Andy Plauche

While defenders were focused on Celestine, Ducote and Armand, Plauche was another force in the backfield.

Even though he wasn’t as flashy as his backfield cohorts, Plauche was instrumental in making the offense work with blocking and giving defenders one more threat to guard against.

Todd Armand

Armand contributed a sizeable chunk of territory as the ‘Cats tough-yardage fullback.

“I was a senior in 1970 and so was Andy Plauche,” Armand said.

At 185 pounds, Armand was also one of the biggest players on the team and was a force to be reckoned with when he came thundering through the line.

He was a tough player. He was kicked out in the first half of the 1970 Simmesport game for allegedly fighting.

Armand and Ducote said the boys on the team were always joking with each other.

“For most of the year, Emile and Todd were tied for who would score the most rushing touchdowns,” Ducote said. “I’d get in the huddle and tell them, ‘I’m not going to give the ball to either one of you. I’m going to keep it myself,’ and then we’d all laugh.”

At some point during the year, Emile broke the tie and ended up with 13 rushing TDs to Armand’s 10.

Armand said he would pick at Emile over his rushing yardage.

With the Wishbone offense, Ducote would keep the ball and roll out, giving him the option of running, throwing or pitching to the trailing tailback.

“When I turned the corner, Emile would turn with me,” Ducote said. “I’d keep my eye on the cornerback because I knew where Emile was going to be. I didn’t have to look for him. I knew he would be there.

“If the cornerback came at me, I’d toss to Emile. If he focused on Emile, I would take off,” he continued. “I pitched to Emile 10 to 15 yards downfield most of the time,” he said.

All yards gained from scrimmage are credited to the last ball barrier, even if he only carried the ball for some of that distance.

“I would tell Emile, ‘Yeah, you got the yards but Steve ran half of them for you -- and then had to take the hit from the cornerback,’” Armand added with a laugh.

Steve Ducote

The quarterback is supposed to be the team’s leader, and by all historical accounts, Ducote fit that bill to a “T” -- a Wishbone T.

"We are running the Wishbone and the quarterback (Steve Ducote) has done a remarkable job," Watson said early in the 1970 season, adding that the 15-year-old quarterback “is an outstanding ball handler and is a heckuva competitor --and a conscientious one, at that."

It was his dedication to becoming better that convinced Watson to make him the starting quarterback when he was only 14.

Watson went on to say the team members “have the greatest respect for him. When he does something, good or bad, he wants to talk about it. He’s always talking football.”

Ducote said that looking back on that time he is still amazed at how well the transition went.

“We had a good time, we worked together as a team, we became good friends,” Ducote said. “I think it is remarkable how smooth we made that change.”

KEY MOMENTS

There were a few key moments that set the tone for the 1970 season.

“We knew Carver was closing and that some of its students would be coming here,” Ducote said. “Coach Watson sent me, Ronnie Brouillette and Rusty Jackson over there at the end of school to meet with them.”

As if sending three white boys into an all-black assembly at a soon-to-be-closed school was not scary enough, Watson told them to wear their football jerseys.

“We walked in and we were nervous,” Ducote said. “They were also nervous, meeting with us. Coach Kelly Fuller came over and was so gracious to us, introducing us. It broke the ice.”

Fuller took a coaching position at Bunkie after Carver closed.

Ducote said several of the Carver players came to practice that summer and four started for the 1970 Wildcats.

“Some of the best athletes that came out couldn’t play for us because they were too old,” Ducote said. “They had used all their eligibility.”

That first day of practice was also a key moment, not only in the season but in the players’ lives.

Ducote said all the white players had arrived earlier and were sitting under a tree waiting for the coach to open the locker room.

“We saw the players from Carver arriving in a group,” he recalled. “They didn’t come over to us and we didn’t go over to them. We just stayed in our two separate groups.

“When Coach Watson got there and opened the door, we all walked in together,” Ducote said. “Outside we had been two groups, but when we entered that door we were one team -- and it has been that way from that day to this one. We made lasting friendships.”